Former Jewish hospital in Wrocław

Ewa Pluta

Until the end of the 18th century, and even into the first decades of the 19th century, medicine in almost no aspects resembled the highly specialised science that we know today. The role of doctors was often performed by various quacks, healers and barber-surgeons, who had little knowledge of not only diagnosis methods and treatment, but even anatomy. Hospitals were more akin to houses of recovery or shelters in which treatment often came down to using a strengthening diet. It was not unusual for medics working in them to base their diagnoses and therapies on the anachronistic theory of “humours”, according to which diseases resulted from the imbalance of body fluids. Attention to hygiene was rare, tools were not washed after subsequent treatments, not to mention their sterilisation. A doctor who had just performed an autopsy would head straight to deliver a baby. The thought of decontaminating his hands would not even cross his mind.

It was not until the 19th century, or rather its second half, that revolutionary changes occurred in medicine as a science and practice of treating diseases and injuries. Undoubtedly, this century was a milestone in the development of medicine, especially in Europe. Of course, it was brought about by many factors, but the most important among them was the flourishing of natural sciences, primarily biology, chemistry and physics, as well as advances in technology. It resulted in many breakthrough discoveries that would forever change the methods of diagnosis and treatment. Basing on related sciences, medicine became increasingly professionalised and specialised. The demographic explosion on the continent also played a significant role. In just 150 years, Europe’s population increased from 163 million (1750) to 408 million (around 1900), resulting in an unprecedented migration from villages to urban centres. It was also evident in Wrocław, which around 1850 had a little over 110,000 residents, and by 1900 this number surged to almost 430,000. It became crucial to organise specialised medical care for this large group of people, which would be based on scientific achievements and capable of prescribing effective treatment. In response to these needs, the modern institution of hospital was created, whose primary role was no longer to provide care to the poor and the elderly (Hospital), but to treat the sick (Krankenhaus). The increasingly impressive hospital complexes were organised according to secular standards, like machines operating efficiently in every aspect.

Although the processes described above affected almost the whole Europe, the greatest successes in this field were achieved by German-speaking countries. In the second half of the 19th century, German and Prussian medicine played a leading role in the world. In 1867 in Prussia alone there were 1,129 modern hospitals, and this number was constantly growing. Against this background, the history of the Jewish Hospital in Wrocław is an excellent example of the development of German and European medicine, but also a symbol of the important part played by Jews in the history of the city.

The history of the Jewish Hospital in Wrocław dates back to 1744, when several representatives of the local Jewish Community founded Chevra Kadischa, a charity society tasked with running Jewish clinics and cemeteries. At the initiative of the society, the first hospital was soon opened in today’s ul. Włodkowica (Wallstrasse) in the Jewish quarter. The small clinic, with only 20 beds, functioned as Hekdesch – the Jewish equivalent of Christian hospices, and like other hospitals in the city at that time, it was a nursing home. In 1841, when there were almost 6,000 Jews in Wrocław (out of the total population of 100,000), a new hospital opened in the vicinity of the former clinic. It was slightly bigger and definitely more modern. Above all, doctors who worked there were educated at universities and held academic degrees. At this point it is worth mentioning that for a long time Jews in Prussia had been allowed to study medicine, but without the possibility of defending academic titles. It was only at the beginning of the 19th century that they were permitted to submit habilitation theses – relatively late, considering that medicine, along with law, was the most frequently chosen field of study by representatives of this community. Considered a liberal profession at that time, it guaranteed employment due to the dramatic shortage of doctors. Graduates could also run a private practice. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, 44% of all doctors registered in Wrocław were Jews. It was an impressive result, considering that the total number of Jews in the city at that time was just under 20,000 out of 400,000 inhabitants.

At the end of the 19th century, it became obvious that the Jewish hospital and several smaller clinics run by Chevra Kadischa were no longer able to treat the growing numbers of patients or meet the increasingly greater requirements of medicine, especially surgery. Therefore, in 1893, members of the society established a fund for the construction of a new hospital, thereby beginning the struggle for the establishment of what would become a magnificent complex of clinics in Wrocław, which for several decades remained the most modern hospital in the city, its medical showcase and a training ground for many outstanding doctors. Although they had no way of knowing it, the place they needed so desperately to help the sick has currently become one of the few surviving traces of the former Jewish Community, which contributed to the development of Wrocław in almost every aspect of the functioning of the urban organism.

During a public collection, which lasted several years, over 2 million German marks was raised. The largest donation was made by the Parisian baroness Clara Hirsch, who donated a huge amount of 300,000 marks. The baroness was an unusual woman. Experienced in running profitable businesses and fluent in several languages, she was also a great philanthropist, supporting initiatives to help Jews settle down in the Americas. She also founded an association that aimed to relieve the overpopulated Jewish districts of New York. Although baroness Hirsch probably never visited Wrocław, it did not prevent her from generously supporting the establishment of this important hospital. Almost one million marks was raised through the so-called Bettstiftungen. Under this scheme, private donors financed comprehensive treatment and care of inpatients occupying a specific number of beds for a period of time. Some chose to finance just one bed, but e.g. Julius Schottländer, a wealthy entrepreneur, financed over 100 beds for many years. It is not difficult to imagine how much money he had to allocate for this purpose each year. A total of 120 people donated funds for the construction of the hospital. All of them followed the Jewish faith, even though it was known from the beginning that the hospital would be open to anyone in need, regardless of their background, religion or financial situation. Most of the donors – local entrepreneurs – are buried in the Old Jewish Cemetery (currently the Museum of Cemetery Art, a branch of the City Museum of Wrocław), in close proximity to the place whose creation they supported so generously.

On 27 April 1903, after just two years of construction, the new Jewish Hospital (Das Israelitische Krankenhaus zu Breslau) was officially opened. A magnificent complex of several buildings was erected on a large plot of land in what is today the Borek housing estate (Kleinburg). The location was no accident. There was already a Jewish cemetery and numerous foundations run by members of the Jewish Community in this area, and many Jewish entrepreneurs and merchants had their villas here. Plans also existed to construct a Jewish school. Undoubtedly, the decision must have also been influenced by the quiet nature of the district, lots of greenery and a relatively short distance from the city centre.

Reinhard Herold, an architect from Berlin, was tasked with designing the entire building complex. Inspired by the famous Heino Schmieden – designer of many hospital premises in Germany, he chose to surround the main edifice with a number of auxiliary buildings: the administrative building, the department of infectious diseases, the dissecting room and the boiler house. In the inner courtyard, a small park was arranged, suggesting that the complex had the character of a sanatorium, which was additionally emphasised by decorative elements whose architecture was inspired by the Silesian Renaissance – the brick façades of the two largest buildings were adorned with wooden details, numerous avant-corps and loggias. The main edifice and the administrative building were covered with high roofs with mansards. The construction was supervised by brothers Paul and Richard Ehrlich, well-known Wrocław architects of Jewish origin. They were also responsible for the subsequent expansions of the hospital in the spirit of early modernism: in 1910, a separate building of the hospice (Arnold and Hermann Schottländer Nursing Home for the Chronically Ill); in 1914, a gynaecological ward along with an ophthalmic department adjacent to the administrative building; and in 1927, the radiology department from the north side of the main building, founded by Nathan Littauer from New York.

When it opened, the Jewish Hospital became one of the largest clinics in Wrocław – a city in which there were already several big hospitals, including the largest of them – a complex of university clinics located in the northern part of the city. The size of a hospital was then measured by the number of beds, and the Jewish Hospital ultimately had over 350, which made it the second largest hospital run by Jews in Germany, after Berlin (370 beds). The third place went to the hospital in Cologne, which had only 180 places for inpatients. Thus, the facility in Wrocław was a real colossus, in which patients were constantly treated in the general, surgical, and later also gynaecological, ophthalmic, children’s and neurological departments. Several dozen assistants lived in the attic flats of the main edifice. Permanent stay at the workplace, shifts up to 14 hours, the obligation to conduct scientific research and a ban on marriages during assistantship were just some of the requirements that young medical graduates had to take into account if they wanted to work in such a prestigious institution as the Jewish Hospital.

Despite these strict rules, there was never a shortage of people willing to work, because for several decades the Jewish Hospital was the most modern medical institution in the city. At a time when many doctors still considered simply washing their hands before surgery as a fad, the hospital introduced rules of conduct aimed at maintaining the sterility of rooms, tools or medicines. The precursor of these standards in Wrocław was the famous surgeon Jan Mikulicz-Radecki. He provided instructions on equipping the aseptic and antiseptic operating rooms at the Jewish Hospital and trained the staff on how to properly maintain hygiene at work. Other facilities at the hospital included separate rooms for sterilising surgical instruments at high temperatures, bathing rooms with showers adapted to the needs of people with disabilities, rehabilitation rooms and very modern laboratories that simultaneously functioned as the hospital’s research and education centre. In 1928, the first X-ray laboratory in Wrocław opened there. Thanks to good equipment and sterility, several innovative treatments were carried out at the hospital. For example, in 1912 the famous neurosurgeon Otfried Foerster transected the spinothalamic tract for intractable pain in a patient with spastic paralysis, which was the world’s first surgery of this kind. Even today this procedure would be burdened with a high risk of complications.

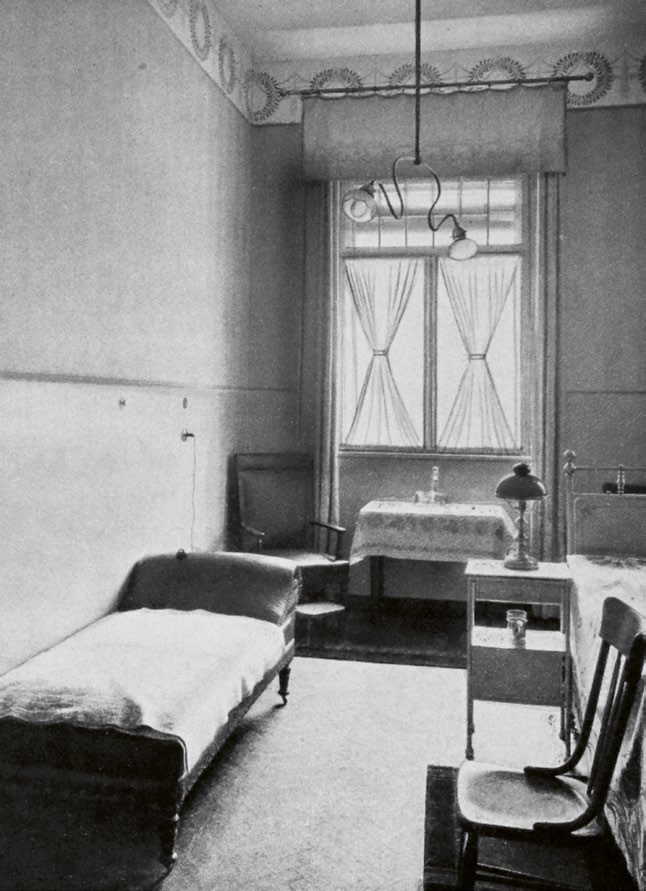

An important change also concerned the approach to patients. Following the example of other hospitals, medical case records were maintained for each patient. During their stay at the Jewish Hospital, inpatients could also could count on comprehensive care from both doctors and orderlies. Convalescents were accommodated in bright rooms with large windows, located in the largest building. First-class rooms were single and their interior design resembled a hotel rather than a hospital; in the second class, there were two beds in a room, and in the third class the rooms had many beds. Patients in the first two classes had to pay for their stay, but in return they could count on better food and even alcohol, if it was not against the doctor’s recommendations. Patients in the third class were admitted free of charge. This solution, alongside the donations for hospital beds, guaranteed a significant inflow of funds for the hospital. When the weather permitted, convalescents could stay on the verandas or in the courtyard park. They could use a library, a games room and a synagogue, which was also available to the inhabitants of the entire district. Doctors and assistants worked in modest offices and met in lecture halls, including the magnificent hall in the administrative building.

Although all the doctors and hospital staff were Jewish, a kosher kitchen was run and Jewish holidays were observed, the hospital admitted all those in need for free. In the opening year, the number of inpatients was 708, and in the late 1920s and early 1930s there were over 4,500 of them, including almost 70% of non-Jews. During World War I, the hospital rescued several thousand wounded soldiers. Interestingly, to lift their spirits, the hospital administrators decided to organise a Christmas Eve for the treated soldiers. Little wonder, then, that one of the annual reports on the functioning of the hospital concluded: “The functioning of our hospital can be an example of an effective measure to combat anti-Semitism and religious hatred.”

Until the complete takeover of the hospital complex by the Nazi authorities in 1938, many prominent doctors had worked in it. The father of the medical achievements of this institution was professor Georg Gottstein (1868–1935), a surgeon and a renowned urologist. Together with Jan Mikulicz-Radecki, he organised and managed the Jewish Hospital during the first years of its functioning. He supervised the training of over a dozen doctors whose future achievements are still used by modern medicine. They included Moritz Rosenstein (1857–1935), a gynaecologist who co-created the principles of functioning of modern gynaecology departments; Fritz Heimann (1882–1937), a gynaecologist, obstetrician and precursor of the use of X-ray diagnostics and radiotherapy in gynaecology; Carl Fried (1889–1956), a diagnostician and precursor of using radiotherapy in the treatment of acute and chronic inflammation; Ernst Sandberg (1849–1917), an internist who devised a programme for the development of general medicine and the principles of functioning of a modern hospital; and finally Siegmund Hadda (1882–1977), a surgeon who was the chief physician of the military hospital in Wrocław during World War I and who pioneered many new surgical procedures.

Beyond doubt, the most famous person associated with this institution was Ludwig Guttmann (1899–1980). The esteemed neurosurgeon devoted his entire life to the treatment of patients with spinal cord injuries, taking this field of medicine to a new level and laying the foundations for its further development. In the years 1933–1938, Guttmann was the head of the neurology department at the Jewish Hospital, and at the end of this period – its chief physician. It was while working here that during the Kristallnacht in November 1938 he saved 60 people from deportation to concentration camps by admitting them as gravely ill patients. After emigrating to England in 1939, as director of the National Spinal Injuries Centre at Stoke Mandeville Hospital, he organised daily activities for his patients, including sports competitions. They grew more popular each year and eventually evolved into the Paralympic movement. During the first Paralympic Games in Rome in 1960, four hundred athletes from 21 countries competed with each other; currently, this number has reached several thousand! In 1966, Ludwig “Poppa” Guttmann was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II for his merits in the field of medicine and his contribution to the development of sport for people with disabilities. Caz Walton, one of Guttmann’s patients and a multiple medallist of the Summer Paralympics, said: “I think Sir Ludwig just changed the world for us; it was a complete step change. He came in, he had a vision. As far as disability and disabled sport was concerned, he did change the world.” He modestly summed up his professional path in the following way: “If I ever did one good thing in my medical career, it was to introduce sport into the treatment and rehabilitation of people paralysed by injury to the spinal cord.” In his memoirs, Ludwig Guttmann repeatedly recalled the years he had spent in Wrocław and the impact of the local medical community on the development of his interest in spinal cord injuries.

During over 30 years of its functioning, the Jewish Hospital managed to overcome the difficulties associated with the admission of thousands of wounded soldiers from the fronts of World War I or the great crisis that broke out in Germany in the 1920s. The next catastrophe, however, was insurmountable. The hardest period for the Jewish community in Wrocław began in 1933. The increasingly harsh persecution of Jews and the prohibition on seeking medical help from them severely affected the condition of the hospital. Some of its staff were arrested during the Kristallnacht, and those who remained in the city after these events quickly decided to emigrate, choosing the United States as their main destination. Three days before the outbreak of World War II, all Jews had to leave their hospital, which the Nazis appropriated together with its equipment. The first thing they did after the takeover was to destroy the symbols of Jewish faith and culture. They demolished the hospital synagogue and rearranged it as a kitchen serving food for the newly established military hospital. The most seriously ill patients were moved to the hospice building, but soon they were forced to leave it too. This is how the history of the Jewish Hospital in Wrocław ended.

During the siege of Wrocław in 1945, the complex of hospital buildings suffered serious damage, which remained visible for several dozen years. It was only after the entire area was acquired by the Polish State Railways that reconstruction began. Renovated and equipped with new facilities, the complex officially opened in 1970 under the name District Railway Hospital. However, the renovation and modernisation negatively affected the appearance of the complex, especially the main building. Red brick disappeared from its facade, and the picturesque high roofs were replaced with flat ones. Today, it is hard to imagine that the main edifice, stripped of its decorative architectural elements, used to resemble sanatoriums in the Giant Mountains. Still, it is surprising that the layout of interiors has remained virtually unchanged since its construction in 1903. Fortunately, the original appearance of the auxiliary buildings was maintained during the rebuilding. Although it never reached its pre-war size, for almost 40 years it was one of the largest hospitals in the city. In later years, the hospital became famous for its Plastic Surgery Ward. Several precursory operations were performed here, including the first abdominal flap-based breast reconstruction and the first sex reassignment surgery in Poland. In 2015, the hospital was definitely closed. Thus history came full circle: the hospital was built over 100 years ago to meet the requirements of modern medicine, and it was closed precisely because it was unable to meet the requirements of modern medicine and its numerous challenges in the 21st century.

Throughout the decades of its functioning, first as the Jewish Hospital and then as the District Railway Hospital, the impressive complex of buildings in the Krzyki district of Wrocław became ingrained in the memory of the former and present inhabitants of Wrocław. It remains an important example of hospital architecture that adds character to the southern part of the city.

illustration source: Das Israelitische Krankenhaus zu Breslau Breslau 1904, private collection

Art Reviev SURVIVAL 17. Catalogue, Wrocław 2019, p. 12-32.